Haiku Poetics: Objective, Subjective, Transactional and Literary Theories

(The Second of Two Parts)

Part 2

Haiku as a Rhetorical Act

In the western tradition, beginning with Aristotle and the Sophists, theories of writing have been constructed by observing the integrated elements of effective communication. As James Berlin explains in his book, Writing Instruction in Nineteenth-Century American Colleges:

Rhetoric has traditionally been seen as based on four elements interacting with each other: reality, writer or speaker, audience, and language.... Rhetorical schemes differ in the way each element is defined, as well as in the conception of the relation of the elements to each other. Every rhetoric, as a result, has at its base a conception of reality, of human nature, and of language. [1].

In A Theory of Discourse, James L. Kinneavy makes a similar claim that writing theories are usually based on "the very nature of the language process itself" [2] that can be expressed as the communication triangle.

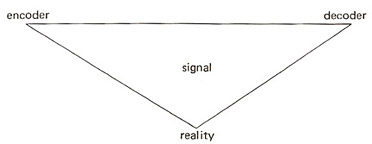

Basic to all uses of language are a person who encodes a message, the signal (language) which carries the message, the reality to which the message refers, and the decoder (receiver of the message). These four components are often represented in a triangle [3]:

I prefer to label the triangle with "writer, reader, language, and reality" and will use these terms to refer to these elements of the communication triangle throughout this essay. When I consider haiku as the rhetorical (or literary) act being considered, I would say that haiku are not "about the writer" yet they include an expressive element that comes from the writer. I would say that haiku are not "about reality" yet they include a context of perception, referring to time (when) and place (where) and things (what) that are presented as images constructing an overall dramatistic scene. I would say that haiku are not "about readers and their values" but invite reader participation in the act of imagination and enjoyment while reading haiku. I would say that haiku are not "about language" but haiku writers and readers enjoy how haiku are written and constructed as literary art, including the wide range of language techniques available. Haiku are a rhetorical act—an attempt by the writer to share with a reader an observation or heartfelt insight referring to a perception or imagination of reality through the use of artistically-constructed language.

In this essay I will explore a variety of approaches to writing haiku—a variety of haiku poetics—seeing how each broad haiku writing theory defines the elements of the communication triangle and the interrelationships of these four elements.

Please understand the importance of the following caveat: there is no "one way" to write haiku, no single haiku poetic or haiku tradition to guide the writing and reception of haiku as a literary art. There is no final list of "do's and don'ts" that will codify the art of reading and writing haiku. Such lists are for beginners being indoctrinated into an approach by their teacher. On the broader level of haiku as a literary genre, we should embrace the observation that there are several ways, a multitude of traditions, a variety of haiku poetic theories. I believe that this variety is essential for the health and vitality of the global genre of haiku.

Broad Categories of Writing Theories

I am eager to get to the exploration of haiku poetics, but first I need to briefly explain the three main categories of writing theories and how each defines reality, favors certain language preferences, and shapes the roles of readers and writers. The three broad categories are: (1) objective rhetorical theories; (2) subjective rhetorical theories; and (3) social epistemic or, more simply, transactional rhetorical theories. Writing theory scholars do not agree on this, but a fourth category would be to treat literature as a unique category of writing theory with its own configuration of reality, readers, writers, and language.

(1) In objective rhetorical theories, reality is defined as the external, material world subject to the laws of nature. The role of the writer is to observe reality as accurately as possible, using our limited sensory perception. The goal is to discover or find the truth and express it without bias or interpretation. Writing based on this approach often is expressed in a plain, scientific style, minimizing the personal pronoun because the focus of the writing is about observed reality. This type of writing theory places a high value on description and accuracy of the revealed truth. The role of the reader is to validate the descriptions and perceptions as accurate without the blurring bias of the writer interfering.

(2) In subjective rhetorical theories, reality is defined as a personal construct of the individual. The goal is to develop and understand yourself and how you have constructed not only your own identity but also your own worldview. Writing based on this approach is usually very introspective and expressive, focused on the self, with a goal of "finding your own voice" and sharing your unique perspective. This type of writing theory places a high value on sharing emotions—letting others into your private, inner world. The writer lets readers see the world through his or her own perspective. The role of the reader is to validate the writer as authentic and genuine in expressing who the writer "really is" through the writing. The sensitive reader connects to or empathizes with the writer's emotions.

(3) In transactional rhetorical theories, reality is a social construct created over time by a community or society and is sometimes referred to as "collective consciousness" or cultural awareness. The goal is to create new knowledge and better understanding through social interaction with others who are likewise collaborating in the social construction of new knowledge and understandings. Writing based on this approach openly invites dialogue (or polylogue) with others both present and from the past, in order to respond to previous work and to collaborate in the creation of new work. The role of the reader is to be an active participant in this ongoing polylogue and the resulting creative response process.

(4) While most scholars include literary texts within these first three categories of writing theories, some scholars consider literary writing to be a fourth category. Those who approach literary writing as its own category would say that literature is focused on imagination and imitation of reality (fiction). Literary writing theory often focuses on language itself as the primary basis for the theory. The role of the writer is to craft an imitation of life with language that engages readers' imaginations. The goal is to create a literary experience through the crafting of artistic language. The role of the reader is to enter into the imagined space of the literary work and to enjoy the artistic craft evident in that work.

Let us consider how these broad writing theories can help us explore and better understand different approaches to writing haiku—to various haiku poetics.

Objective Haiku Poetics

Objective haiku poetics emphasize the importance of reality, usually referred to as nature. The haiku moment is characterized as an instance of sensory perception of reality, without the blurring lens of human values or perspective. On a larger scale, the movement of thinking is from the observation of particulars about reality (or nature) to broader universal truths (the nature of nature) that is often viewed in haiku as universal seasons. The writer is present as an "everyman" representative of human beings in general, perceiving nature (or reality) without interpretation, explanation, commentary, or emotional response. The writer is supposed to be ego-less, so that the haiku will be about the thing observed instead of the observer. The goal is to show things "as they are" without interpretation or emotional coloring of significance.

Often a plain style is favored as the most effective language for this approach, so that the language is not distracting the reader from the reality being observed. Sometimes this style of language is characterized as "transparent" or "clear" as if you were looking through a window but forget that the window is there. Like the writer, the language is supposed to disappear as the reader recognizes the truth of the observation—"yes, that's the way it really is."

At the turn of the twentieth century, Masaoka Shiki called for a rejuvenation of haiku through a "shasei" approach which emphasized "realistic observation of nature rather than the puns or fantasies often relied on by the old school" [4]. He viewed the earlier approaches as antiquated literary traditions with too much emphasis on cliché subjects, stilted poetic language, and a focus on imaginary literary or artistic scenes from the past. As a war correspondent in China, he wrote haiku such as [5]:

The summer river:

although there is a bridge, my horse

goes through the water.

The role of the reader in objective haiku poetics is to become an "everyman" reader who imagines themselves re-living the experience of reality—the observation of nature being portrayed through the images of the haiku. The reader "steps into" the writer's "everyman" perspective and imaginatively observes what the writer observed.

Subjective Haiku Poetics

Although Shiki called for "sketches from life" and Kiyoshi expanded that to the "objective sketch" approach to haiku, Shiki is most beloved for writing poetic diaries throughout the course of his fatal illness. For example, in a sequence called "Snow While Sick" Shiki wrote [6]:

again and again

I ask how high

the snow is

As part of his autobiographical diaries, this haiku is clearly about Shiki and his limited perspective of the snow from his sickbed. More than an objective description of reality, it is a portrayal of his existence and his frustrated perspective of being sick. The overall effect for the reader is to imagine Shiki lying in the bed, and with some imaginative empathy, we become the person he is asking again and again "how high the snow is." Shiki is the subject of this haiku and the language conveys his attitudes and inner emotions. This is an excellent example of a haiku written from a subjective haiku poetics approach.

Subjective haiku poetics emphasize the inner world and life of the writer. The haiku moment is characterized as an instance of self-awareness about the feelings and significance of "being in my own world." When a collection of haiku is published by a writer in this tradition, these lived moments of insight and self-awareness often become a poetic autobiography. The writer explores his or her own identity and life's experiences through haiku, writing about themselves, their family, their home town, their culture. Many haiku writers in this tradition embrace haiku as therapy or as a means of spiritual growth through meditation and self-contemplation.

Subjective haiku writers often embrace opportunities to employ idiosyncratic language or playful language resulting in a unique voice. Among the Japanese haiku masters, Issa immediately comes to mind as a poet who wrote autobiographical haiku with a playful voice fitting his Buddhist perspectives and values. For example [7]:

Lean frog,

don't give up the fight!

Issa is here!

Although writers employing subjective approaches appear to use language that is spontaneous or conversational, most carefully craft their haiku to create a voice with the illusion of spontaneity and intimacy. The subjective haiku writer hopes readers are very interested in his or her life and wants readers to accept his or her haiku as genuine, authentic expressions of the writer's inner world. The subjective writer pretends to ignore the readers, as if the readers aren't really examining what the writer is experiencing. The writer wants to be "true to herself" and not pander to the desires of readers. The overall goal for subjective haiku poetics is for the writer to convey heartfelt responses to being alive in his or her own worldview.

The role of the reader in subjective haiku poetics is to get to know the writer and the important moments of insight and feeling they express through their "bits of life" haiku. The reader seeks to understand the writer's perspectives and attitudes. The reader doesn't "enter into" the writer's perspective, but instead lurks outside the writer's life as if he or she is spying on the inner secrets and experiences the writer is going through. There is often a sense of becoming an intimate friend to the haiku writer, because the reader is given access to the inner thoughts, feelings, and concerns of the writer. The reader doesn't have to become Shiki to understand and feel the frustrations of a limited sickbed life. Writer-based haiku are often enjoyed because the reader does not have to take the writer's perspective. The haiku are so focused on the writer's life and feelings, there is little room left for the reader.

In literary theory, subjective haiku poetics is similar to the poetics of the Romantic poets who were admired as individuals with unique sensibilities and expressive capabilities. This theory tends to view the best writers as more gifted and talented than others by their innate nature. Readers are encouraged to explore their own inner thoughts and feelings, therefore developing their own individualistic sensibilities and artistic abilities by writing subjective haiku about their own lives like those admired by favorite writers.

Transactional Haiku Poetics

Transactional haiku poetics emphasize the social nature of haiku as a call and response process of creative collaboration between the writer and reader. The haiku moment is characterized as a union of reader and writer who meet in a beloved haiku as co-creators of the felt significance of the poem. This approach seems especially fitting to haiku traditions, given haiku's origins as the hokku, or starting verse, in Japanese linked poetry.

In transactional haiku poetics, reality is socially constructed as images and language connected to culturally shared memories and experiences (a community's shared collective consciousness). Language is also viewed as a shared social construct, with culturally sensitive word choice and phrasing being another primary means of sharing significance between writer and reader.

The reader relates to the images in the haiku through his or her own memories and associations with the things mentioned in the poem, in order to create their own felt experience and understanding of the haiku moment. The transactional haiku poetics place a high value on reader response—sharing the imagined experience of a poem with others, including the writer. A variety of responses and associations are expected from a variety of readers. The joy of haiku is in sharing this variety of reader responses, and, of course, one possible response is to write a haiku in response to a previously enjoyed haiku. In other words, this approach values the linking process—connecting to haiku others have written before, yet creating new haiku that shift beyond previous haiku. As collaborative readers and writers of haiku, we revisit haiku from the past and collaborate in the process of making them new for the present in our own time and culture.

This social collaborative process works within the form of haiku as well. The cut or "kireji" of haiku provides a miniature version of the linking process. A haiku begins with one image or phrase that stimulates a reader to anticipate what is coming next. In that silent pause between the first and second part of the haiku, the reader enters into the haiku's space, imagining and feeling the initial associations provided. Then the reader finishes reading the second part of the haiku and considers how that image or phrase alters their previous expectations. The reader then re-reads the entire haiku, letting it expand out into possible readings, associations, memories and points of felt significance.

The role of the reader in transactional haiku poetics is to be a co-creative, collaborative partner. The writer starts the process and the reader completes or fulfills the creation of meaning or feelings elicited from a haiku. The reader is expected to be a socially responsible partner, entering a haiku's gift of shared consciousness. The transactional haiku poetics depend on the active cooperation of a good reader. To be a good reader requires a certain amount of trust and expectation that both writer and reader understand and appreciate the arts of reading and writing haiku.

Literary Haiku Poetics

Obviously literary haiku can and have been written based on the objective, subjective and transactional theories of writing. In fact many writing theory scholars would argue that all haiku are necessarily written from one of these three broad theoretical approaches. However, some scholars claim that literature is a special category of writing and should therefore be considered a fourth broad approach. I indulge those scholars and include literary haiku poetics as a fourth approach to haiku poetics, although I agree that literary haiku poetics is actually a subset of concerns within the other three theories, primarily addressing issues about language and fiction.

Literary haiku poetics emphasize language, through which the writer crafts an imaginative stage of possibilities—a fiction.

The writer crafts a literary artifact with all of the linguistic tools and imaginative resources available in his or her poetry toolkit. The haiku moment is characterized as an experience of the poem itself—its sound, its structure, its images, its characters and its overall felt significance. Literary haiku are written from memories, experiences, imagination and other works of art. Some literary haiku are episodic, capturing a scene from other literary works, art, movies, popular locations, rituals, holidays and songs. Other literary haiku are narrative, written from a fictional writer's voice and perspective. There is a long-standing tradition of "haigo" or haiku identity in the Japanese traditions. A few American haiku writers, for example Raymond Roseliep, have employed such haiku narrators. Recent haiku novels, such as Haiku Guy by David Lanoue, create a group of semi-fictional haiku writers engaged in the art of haiku.

As anyone who has participated in linked verse writing knows, the hokku may be directly tied to the events, immediate experiences, specific location and season of the gathering, but all subsequent links are imaginative creations. They are fiction, created to be realistic or fantastical depending on the imaginative movement of the collaborative participants.

A wide range of language is employed in literary haiku, depending on narrative voice and the variety of language that is an experience in itself. As a language-based approach, literary haiku enjoy playful language employing puns, slant rhyme, alliteration, allusions, implied analogies, metaphors and other poetic techniques.

Sometimes literary haiku appear to ignore the reader, favoring dense, oblique language that celebrates ambiguity or abstraction. The goal is not to be realistic, but to provide readers with a language-intensive experience. Although a wide-range of works fall within the literary haiku poetics, some, like abstract paintings, deliberately attempt to avoid any apparent reference to reality. The primary goal of literary haiku is to be an engaging literary artifact with an immediate aesthetic experience and lasting resonating value to readers.

Buson's famous haiku about the "dead wife's comb" is an excellent example of an imaginative literary haiku translated by Harold G. Henderson [8]:

The piercing chill I feel:

my dead wife's comb, in our bedroom,

under my heel . . .

This haiku expresses an emotional response to an imagined experience. It is written as if it was an actual experience, but as R. H. Blyth noted in The History of Haiku, "In actual fact, Buson's wife Tomo died in 1814, thirty four years after this verse was composed in 1780" [9]. Therefore the haiku is written from a fictional narrator, based on an imagined experience, resulting in a engaging and emotional literary artifact.

The role of the reader in literary haiku poetics is to imagine the feelings and perspectives of characters in a fictive scene. Instead of imagining themselves as a fictive self re-living the writer's experience of reality, literary readers enjoy a more external audience perspective observing things happening on the haiku stage. The reader maintains the perspective of the audience outside of the events unfolding in the literary artifact. In this approach, good readers know the literary haiku tradition, including allusions to other poets and other well-known haiku. The reader appreciates the craft of the haiku as a literary artifact, including language usage and style choices. The role of the reader is to judge the literary quality of a haiku—does it have lasting value beyond the first reading.

Extreme Disjunctions of the Communication Triangle

I would like to briefly note attempts to develop haiku poetics based on extreme disjunctions of the communication triangle. These approaches attempt to guide the art of haiku by deliberately omitting or ignoring one of the key elements of the triangle—writers, readers, language, or reality. The results have often alienated readers and have rarely resulted in high quality haiku that have value beyond being a "tour-de-force" for the attempted approach. I consider these to be interesting experiments for alternative approaches to the creation or reception of haiku.

(1) Writer-less haiku. There have been several attempts to develop "random haiku generators" in which a database of phrases and images are randomly combined to generate new haiku. This has been a popular computer programming assignment in universities, resulting in randomly created haiku. Without a writer, these haiku lack the intuitive connections and artistic choice of words expected in haiku. Based on a shallow understanding of the haiku traditions, these random haiku generators create lines of 5-7-5 syllables, but the resulting haiku are nonsensical or chance accidents of enjambment. They lack emotion and connotations usually found in haiku. The role of the reader is to see if any of the random creations "seem to make sense" or appear as if they could have been written by a human. Ultimately, the goal is similar to the "Turing Test" in artificial intelligence—could a human tell which haiku were written by a human or generated by a random computer program? For all of the randomly generated haiku I've seen, it is easy to tell that they are not as good as attempts to write haiku by beginners.

(2) Wordless haiku. There have been experimental attempts to write haiku without verbal language including: typewriter art haiku, wordless visual haiku, and the infamous fictional character, the white poet, Shiro, in David Lanoue's novel Haiku Guy [10]. What better way to eliminate the writer's ego than for a haiku poet to merely think his or her haiku instead of writing them down? Of course, such an egoless poet will never have more than one reader (only the poet will experience his or her own thought haiku). And thinking haiku doesn't have to be in words. It can be completed in mere "dibbits" of thoughts and images without the need to translate such thoughts into communication conventions. The typewriter art and wordless visual haiku usually employ kireji, the haiku cut, portrayed visually as a juxtaposition of images. In all of these cases, the role of the reader is to puzzle out what the poet might have been thinking or how the visual images interact with each other on the page.

(3) Language-only haiku. With no realistic nor imagined scene, what happens in language-only haiku is an experience of language. The language-only haiku approach attempts to deny the referential nature of language by omitting reality from the communication triangle. Of course it is impossible to eliminate all referential elements in language, unless the writer eliminates all nouns, most verbs and all sensory images from the haiku, so many of the language-only haiku appear to be a mix of images, abstractions, generalizations, adjectives, adverbs and surprising analogies or metaphors. Metaphors and analogies usually include at least implied referential elements, so it is nearly impossible to write a pure language-only haiku. A random accumulation of abstract words or collage of words layered on each other might be the exception. The main goal is to focus on language itself as the primary subject of language-only haiku. The writers enjoy playing with language and finding hidden nuances and new meanings through surprising juxtapositions and unusual enjambments of language. The only thing that is real in language-only haiku is language itself. The role of the reader is to experience the surprising constructs and enter into an exploration of language events. The haiku moment is primarily an experience of language outside the norms and conventions of language usage.

(4) Haiku as merely form. In the haiku community we are all aware of the popular conception of haiku as a closed form in which the defining characteristic is the 5-7-5 syllable count for a three-lined poem. This form-only approach to haiku ignores the various ways that haiku traditions typically define reality, language, and roles of writers and readers. Instead of being informed by the haiku traditions, according to this approach anyone can write a haiku with any possible content as long as the language is organized in three lines with 5-7-5 syllables. The result of this approach is that we see many mainstream poets "dabble" in haiku by writing the same things they always write, but organizing it into three line verses of 5-7-5. We see popular culture topics such as vampires, werewolves and computer jokes "turned into haiku" because they follow this form-only guideline. The writer's conception of the poet as "wisdom speaker" is often carried over into this form, resulting in several collections of so-called haiku that convey the writer's maxims or "philosophical" wisdom statements in verse with 5-7-5 lines. Although these form-only haiku do not usually hold up for repeated reading, the humorous popculture form-only haiku can be funny as content the first time they are read.

(5) Writer-only haiku. Not the same as wordless haiku, this approach emphasizes the importance of haiku as a cognitive process in the writer's head. The writer-only haiku attempts to block readers from participating or interfering with the writer's cognitive processes. The writer resists or protests social norms and conventions of reading haiku—forcing the readers out of their usual expectations and processes. The writer-only haiku captures the sudden shifts and leaps of consciousness—not as a stream of consciousness but as breaks and disjunctions of thoughts. The goal is for the haiku to capture dream-like movements, surreal shifts, and unusual turns of thought out of the ordinary use of language. The writer-only haiku may be puzzling or disturbing to readers so much so that it could be called the anti-reader approach to haiku. It appears to be a club with NO READERS ALLOWED! Sometimes the goal is to repel or to shock the reader out of their usual social or political or cultural comfort zones. If the goal is to keep readers out of the writer's head, the result may be similar to the fate of the white poet—the writer will succeed at exploring their cognitive states of being and end up writing primarily only for his or her own head.

(6) Reader-less haiku. See all of the previous five approaches that deliberately attempt to omit one or more of the key elements of the communication triangle.

Conclusion – Does Haiku Poetic Theory Matter?

In the contemporary haiku community, most of us write not by following a theory, but through an intuitive sense of quality and imitation. We write haiku like the ones we've enjoyed. We want readers too, so we submit our work for peer review and publication. We share our haiku in small social groups and enjoy hearing each other read at gatherings of haiku poets. The responses and feedback we receive from our friends, editors and readers help shape our approach to writing haiku. So for the most part, we develop an intuitive "tacit" theory of how to write what we come to view as high quality haiku. As writers we form our own internal monitors and guides to writing haiku.

My goal in writing this essay on various approaches to haiku poetics is to help haiku writers examine their own assumptions—to help writers discover and become more aware of their own tacit theories, therefore making their choices and approaches more explicit. Understanding how our own approaches relate to long-standing traditions provides writers and readers with a vocabulary for discussing this rich variety of approaches. Understanding theories of writing haiku helps us understand and appreciate the rich diversity of haiku traditions and how each approach has its own goals, aims, epistemology, conception of reality, roles for writers and readers, and its own subsequent examples of excellent haiku. Theory helps us value the different approaches enriching the genre, so that we are not narrow in our conceptions of haiku. It should also help the haiku community be less susceptible to pundits who want to proclaim his or her own haiku poetics as the one and only way.

The haiku community has matured beyond the beginner's need for definitions and "do and don't" rules. We celebrate the diversity of a global haiku genre that is rich and strong only to the extent that there is a wide range of practice and a surprising freshness of voices and perspectives. We embrace and celebrate: haiku writers who relish dense language and the naming function of words; haiku writers who live in the woods and tap into the biodiversity of ecosystems; haiku writers who protest social injustice and go to jail; haiku writers who resist male ego dominance; haiku writers who meditate and seek a quiet voice within themselves; haiku writers who celebrate being social and the significance of being in community; haiku writers who are religious within a variety of spiritual traditions; haiku writers who are all about people; haiku writers who write senryu and don't care about the distinction; haiku writers who are international citizens of the world using haiku to bridge cultures; and haiku writers who are so local nobody but friends at the local pub can understand them. This diversity of writers and approaches to haiku is the source of strength, health and rich elasticity found in this thriving literary genre.

•

Endnotes & Works Cited

[1] James Berlin. Writing Instruction in Nineteenth-Century American Colleges. Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984, pages 1-2.

[2] James L. Kinneavy. A Theory of Discourse. New York: W. W. Norton, 1971, page 18.

[3] James L. Kinneavy. A Theory of Discourse. New York: W. W. Norton, 1971, page 19.

[4] Janine Beichman, Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works, Boston, MA: Cheng & Tsui Company, 1986, page 45.

[5] Harold G. Henderson, An Introduction to Haiku: An Anthology of Poems and Poets from Basho to Shiki, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1958, page 177.

[6] Janine Beichman, Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works, Boston, MA: Cheng & Tsui Company, 1986, page 65.

[7] Harold G. Henderson, An Introduction to Haiku: An Anthology of Poems and Poets from Basho to Shiki, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1958, page 133.

[8] Harold G. Henderson, An Introduction to Haiku: An Anthology of Poems and Poets from Basho to Shiki, Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1958, page 113.

[9] R. H. Blyth. A History of Haiku: Volume 1, From the Beginnings to Issa. Tokyo, Japan: Hokuseido Press, 1963. Seventh printing, 1976.

[10] David Lanoue. Haiku Guy. Winchester, VA: Red Moon Press, 2000.

![]()