Haiku Society of America

.haiku column

The Haiku Society of America is pleased to host this ongoing column.

.Haiku: a place to share tools available to haiku writers and fellow haiku fans (like how to use Twitter, Facebook and Scribd for building community, self-publishing and marketing). The column will also feature interviews, blog spotlights and occasional multimedia presentations.

Gene Myers

~ ~ ~

.haiku column 31

.haiku column number 31 • 10-29-2015

by Gene Myers <poetgene@gmail.com>

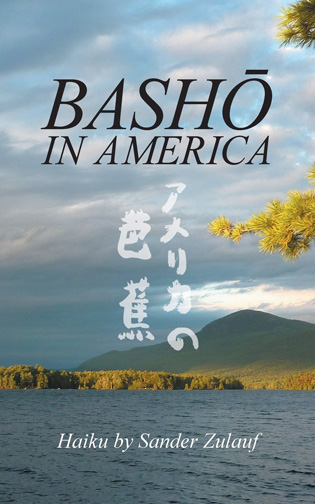

"Basho in America" — one poet's spiritual journey

One thing that I would love to see more of is an appreciation of haiku coming from the larger world of general poetry. Why on earth this doesn't happen I can't say. But poet and professor Sander Zulauf came up with a great answer to that question in the following interview.

Zulauf was my professor in college, and I owe him a lot. He taught me about literary giants, like Langston Hughes and Robert Frost. There were also little asides like how to count the chirps of a cricket to get the current temperature. He added a depth to my life for which I can never thank him enough.

Between his spiritual approach to life (he was named the first Poet Laureate of the Episcopal Diocese of Newark, N.J. in 1999) and his penchant for conciseness, it makes sense that he would eventually make his way to haiku.

This interview focuses on that journey and the time he dedicated to following in the footsteps of haiku's patron saint, Matsuo Basho. While Basho was inspired by Lake Biwa in Japan, Zulauf holed up in Lake George, New York. Zulauf's latest book is "Basho in America."

Q: It seems like a transformation has taken place in the process of writing this book. Does that ring true for you? If so, what kind of change, and when did you realize that it was happening?

A: While at the Dodge Festival in Newark in 2012, the Haiku Society [of America] had a table there and the woman at the table told me about the thousand mile hike around Japan that Basho made in the 17th century. I got interested in Basho and wanted to learn more and soon I applied for a sabbatical from teaching with the idea that I would go to Japan and China and Chile to translate the ancient Chinese poets, Basho, and Neruda. It turns out these poets influenced [Chilean poet Pablo] Neruda.

When I saw Basho's Lake Biwa on the Internet, it reminded me of Lake George. I began reading Bill Higginson's "The Haiku Handbook," the Cor van den Heuvel anthology you gave me, Robert Hass's "The Essential Haiku," Jane Reichhold's masterpiece "Basho The Complete Haiku," and the hugely wonderful book by Sam Hamill, "Narrow Road to the Interior."

During the summer of 2013 I made arrangements to rent a cabin on an island in Lake George and began writing some of the haiku that would end up in "Basho in America." That cabin became my "abode of illusion" and the experience turned into the happiest writing week of my life. It was definitely a transforming experience for me as a poet.

Instead of translating Basho, I first started writing transfigurations of his haiku. It resulted in my first published haiku in the Stillwater Review, which evolved from a transliteration of a Basho haiku by my Japanese scholar friend David A. Heinlein. That poem never made it into my book, because I found that the world is filled with Basho translations. (You can find 40 or so translations of his famous "frogjump" haiku on the Internet). So I set off in a new direction and decided to use Basho's haiku and prose as a doorway or portal into my own original haiku.

I had always been convinced that compression and conciseness and imagery were the keys to excellent poetry, following the clarity and simplicity of the work of my original inspiration to be a poet, New Jersey poet William Carlos Williams, but did not experiment with haiku in my own poetry. When I finally did, it seemed like the most natural thing in the world. To make something happen (in spite of Auden's famous poem's last line) in three lines of poetry was a breakthrough for me. I have not written more than a dozen haiku since the book came out, and have returned to my more usual narrative explorations of the lyric, concentrating on lines, and music and rhythm and image to get the job done (which may have been the result of my translation of Neruda's book, which also has hundreds of translations out there). So perhaps "transformation" into a haiku poet is not exactly what happened to me—I figure that I was just exploring a form with more joy in writing than I had experienced in a long, long time.

During the rest of the sabbatical, I translated one Chinese poet (Wang Wei) with the help of a native Chinese speaker and writer named Jennie Cho, and in the spring of 2014 traveled to Chile and South America and visited all three of Neruda's houses there after translating his first book of poems "Twenty Love Songs and a Song of Despair," which is still waiting for me to get to a publisher.

Then in September of 2014 "Basho in America" was published . . . I learned that it's been honored as a finalist in the 2015 Eric Hoffer book awards. Madeline's [Zulauf] photograph on the cover looks like Mount Fuji, but actually it is of Black Mountain, the tallest peak in the Lake George region. (Basho speaks of "Feather Black Mountain," and many of the scenes in his prose and poetry match scenes and place names in Lake George—pine trees, islands, hermit huts). Mostly you know my fascination with Nature as my subject and my love of Lake George since I was a pre-teen, and that too made that week in September 2013 on Fourteen Mile Island one of the happiest experiences of my life.

So, the short answer would be certainly a transformation took place in the writing of this book, but I would say I have not been transformed into a haiku poet. It's more the personal realization that haiku has enlarged my experience and added to my joy in life as a poet.

how foolish!

to think i am

bashô

Q: For some reason even the most famous of poets—people who know the various forms and meters in their sleep—totally botch the intricacies of haiku. But not you, you went for it and you did your research . . . Any idea why it's so widely misunderstood, even amongst poets?

A: Why is haiku misunderstood? Why is everything these days? Everything can be known instantly, but very little is understood any more. Maybe because haiku is so minimalist a form people tend to shrug it off like rain on umbrellas—something to be protected from rather than engaged with. Great poets are considered great if they write epics, the long poems that go on and on like Chaucer, Dante, Milton, Wordsworth, Whitman, Homer, of course, & Virgil. Then the lesser honored poets are masters of the lyric, but their names come up much less frequently. And among haiku poets, Basho, Buson, Issa and . . . few if any American names show up there. So why invest in something that is guaranteed to be looked at as lightweight, especially in a society where poetry has such little respect, unless it is connected to a song, which makes it something else.

So much of haiku seems to go nowhere, as if that will make it more profound. And the first thing people try to do when encountering haiku by reading it or writing it is to pay careful attention to the meter and lines and the rules, the kigo words, the tradition, and get so hung up with the technicalities because they are learning the tradition, that when mastery comes also comes the fear of failure unless they continue to follow the rules. But I found many writers successfully breaking away from all the rules and traditions and realizing that haiku has to come out of life and living if it is ever going to make a difference to anybody. Then the shared experience of poem with poet and reader—what I try to suggest in my "moon viewing party" poem on the back cover (and there only—not in the book itself)—is my theory of poetry—two solitary beings experiencing the same thing, one at a time. Which also honors the tradition of the "moon viewing party" and the creation of haiku with Basho and his students.

Could that be why? The problem with this age? So much to know we forget to live?

Q: As you were investigating haiku was there something about the form itself that surprised you, something you didn't know previously?

A: My trip through haiku-land began with the challenge of working with the westernized version of three lines and 17 syllables. That discipline with syllable count made word choice extremely difficult, trying to juggle and tame sound, sense, rhythm, meaning and syllables with the exact word all at once to make something viable to experience. When I looked at the many English translations of Basho and Issa and Buson, I realized that modern translators let the rigidity of the haiku form drop away as easily as autumn leaves. There is freedom working through the discipline, and when the worry over making all the syllables dance in perfect lockstep to a three line "cha-cha-cha" dissipates, I found my way to making sounds that make sense as well as resonate with imagery and insight and stopped obsessing over the perfection of syllable count. Then I decided to write exclusively in lower case and in Italics. There are a few capitalized letters in "Basho in America" —an "I" and "God" and "Zen"— and I placed the poems on the pages by indenting each one in descending order to emphasize its complete experience as a poem. I had to fight editorially for all of these decisions, and the result is a book of haiku that is unique.

• • •

Is there something you would like to see in a column? Email me at <poetgene@gmail.com>.

• .haiku column number 31 • 10-29-2015 •

~ ~ ~